An Overview of Aikidō & Aikibujutsu

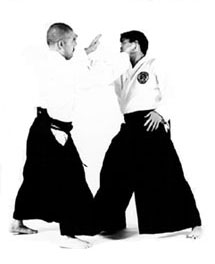

Aikidō's fundamental principle is to blend with an opponent's movement and energy, controlling his or her physical center while protecting one's own center against reversals. One neverfights strength and aggression with the same, but rather relies on more refined techniques and methods, such as tai sabaki (body movement), kansetsu-waza (関節技; joint locks), kuzushi-waza (崩し技; off-balancing methods), nage-waza (投げ技; throws), osae-waza (抑え技; controlling techniques), kyūsho no jutsu (急所の術; vital-point attacks), and, of course, aiki (blending of movement and energy) to effortlessly redirect, neutralize, or control an opponent's attack.

Ueshiba Morihei-sensei; photo taken when he was still teaching Daitō-ryū Aikijūjutsu |

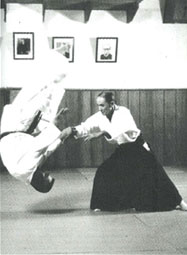

Obata-sōshihan's aikidō stems from the techniques of Shioda Gōzō-kanchō (founder of the Yoshinkan Aikidō Dōjō) as they were handed down to him by Ueshiba Morihei-sensei, the founder of aikidō. Shioda-kanchō learned aikidō (referred to as aikibudō during his earlier years of training) during the pre-WWII era. However, Ueshiba-sensei's deep involvment in the esoteric Ōmoto-kyō (大本教) sect of Shintō and his varied experience later profoundly altered the art into something more philosophically minded (and less practically minded) — an approach the Yoshinkan branch did not subscribe to.

The late Shioda Gōzō-kanchō of the Yoshinkan Dōjō occupied a prominent place in the Japanese martial arts community. Obata Toshishiro-sōshihan was one of the last generations of traditional uchi-deshi to have trained under Shioda-kanchō. Obata-sōshihan continues to pass on aspects of the combat-effective techniques that he acquired as a member of the elite Yoshinkan professional instructors group through his own aikidō organization, the Aikidō & Aikibujutsu Tanren Kenkyūkai.

The late Shioda Gōzō-kanchō of the Yoshinkan Dōjō occupied a prominent place in the Japanese martial arts community. Obata Toshishiro-sōshihan was one of the last generations of traditional uchi-deshi to have trained under Shioda-kanchō. Obata-sōshihan continues to pass on aspects of the combat-effective techniques that he acquired as a member of the elite Yoshinkan professional instructors group through his own aikidō organization, the Aikidō & Aikibujutsu Tanren Kenkyūkai.

As a result of the Yoshinkan's early (pre-WWII) development, a large number of the original jūjutsu techniques were faithfully retained in the inner curriculum, many of which are technically similar if not identical to Daitō-ryū Jūjutsu (as seen in Ueshiba Morihei's Budō Renshū, a catalog of transmission or mokuroku that was issued to some of his senior aikibudō students).

Obata-sōshihan trained as an uchi-deshi under Shioda-kanchō for seven years, learning the lesser-known older techniques preserved within the Yoshinkan. Obata-sōshihan later created the Aikidō & Aikibujutsu Tanren Kenkyukai, of which the aiki methods are sometimes catagorized as a “hard style” of aikidō. However, this branch of aiki is somewhat unique in its ability to remain effective at faster, realistic speeds, while retaining fluid “aiki-type” movements. In other words, “soft methods” (exercises and techniques common to modern aikidō) are taught in addition to the “hard methods” (jūjutsu kihon waza) in order to offer the student a well-rounded education. (Please see the curriculum page for more information on our approach.)

Obata-sōshihan trained as an uchi-deshi under Shioda-kanchō for seven years, learning the lesser-known older techniques preserved within the Yoshinkan. Obata-sōshihan later created the Aikidō & Aikibujutsu Tanren Kenkyukai, of which the aiki methods are sometimes catagorized as a “hard style” of aikidō. However, this branch of aiki is somewhat unique in its ability to remain effective at faster, realistic speeds, while retaining fluid “aiki-type” movements. In other words, “soft methods” (exercises and techniques common to modern aikidō) are taught in addition to the “hard methods” (jūjutsu kihon waza) in order to offer the student a well-rounded education. (Please see the curriculum page for more information on our approach.)

The Roots & History of Aikidō

Unfortunately, the exact origin of the root arts and forms that serve as the foundation of modern aikidō have not been documented completely, and as such there are several popular theories that are in circulation currently. The version provided below closely follows the oral tradition of the history.

In its earliest form, it is believed that aikidō technique originated with Shinra Saburō Minamoto no Yoshimitsu, a famous samurai of the Seiwa Genji-han (descended from Emperor Seiwa), approximately 900 years ago. It is said that Yoshimitsu and his brother Yoshiie dissected and analyzed the bodies of criminals and war dead at their home, Daitō (大東) Mansion, and with this understanding of anatomy and skeletal mechanics formed the basis of the Daitō-ryū (大東流) style of jūjutsu. Yoshimitsu passed the art to his son Yoshikiyu, who later moved to the territory of the Takeda clan. Yoshikiyu's family line resided in Takeda-controlled Kai Province (modern-day Yamanashi Prefecture) from the 1500s to the late 1800s and came to assume the family name of “Takeda” and the Kai-Genji Takeda lineage.

Takeda Sōkaku & Daitō Ryū

Originally, aikijutsu had been developed as a combat art based primarily on tōsō techniques (刀槍; sword and spear) to be used on battlefields against other bushi (武士; warriors) wearing armor. At the time, jūjutsu was practiced as a secondary study to the weapons arts. Within this type of jūjutsu were additional levels of training, called aiki no jutsu and aikijūjutsu, that were reserved for the higher-ranking samurai. The jūjutsu techniques could be used offensively, while the aikijutsu was strictly designed to be a defensive art. The techniques evolved with the needs of the times and were handed down eventually to the aforementioned Kai-Genji Takeda family in the 16th century as gotenjutsu (御殿術; court martial arts). Takeda Kunitsugu, founder of the Kai-Genji line and Aizu shinan-ban (sword teacher to the Aizu clan), passed on the teachings to qualified members within the Aizu clan. Top retainers, lords, and generals of Aizu learned aikijutsu as a defensive art to be used while working within Edo castle (an art also referred to as hanza handachi and oshikiuchi). Hoshina Masayuki, an instructor to the fourth shōgun, Tokugawa Ietsuna, at Edo castle, is said to have completed development of this art of oshikiuchi, which was later reunited with the Takeda family's traditions in the Meiji period and become known eventually by the name Daitō Ryū.

Originally, aikijutsu had been developed as a combat art based primarily on tōsō techniques (刀槍; sword and spear) to be used on battlefields against other bushi (武士; warriors) wearing armor. At the time, jūjutsu was practiced as a secondary study to the weapons arts. Within this type of jūjutsu were additional levels of training, called aiki no jutsu and aikijūjutsu, that were reserved for the higher-ranking samurai. The jūjutsu techniques could be used offensively, while the aikijutsu was strictly designed to be a defensive art. The techniques evolved with the needs of the times and were handed down eventually to the aforementioned Kai-Genji Takeda family in the 16th century as gotenjutsu (御殿術; court martial arts). Takeda Kunitsugu, founder of the Kai-Genji line and Aizu shinan-ban (sword teacher to the Aizu clan), passed on the teachings to qualified members within the Aizu clan. Top retainers, lords, and generals of Aizu learned aikijutsu as a defensive art to be used while working within Edo castle (an art also referred to as hanza handachi and oshikiuchi). Hoshina Masayuki, an instructor to the fourth shōgun, Tokugawa Ietsuna, at Edo castle, is said to have completed development of this art of oshikiuchi, which was later reunited with the Takeda family's traditions in the Meiji period and become known eventually by the name Daitō Ryū.

Takeda Sōkaku was raised in the Meiji era (1868-1912). At this time, the Meiji Restoration was underway, and major changes were occurring throughout Japan that involved the assimilation of Western ways and the expansion of international trade agreements, as well as the elimination of the feudal class structure (including the dissolution of the samurai class) to ensure that all people would be treated equallythereafter. Among changes made during the Meiji Restoration was the Haitōrei, a ban on the wearing of swords publicly, passed in 1876. Seeing the effects of these new changes, Saigō Tanomo, believed to have instructed Sōkaku in the art of oshikiuchi, advised Sōkaku to shift the emphasis of Daitō Ryū* from its primary kenjutsu (劍術; swordsmanship) basis to that of aikibujutsu, which has a taijutsu (体術; unarmed technique)basis. As a result of these changes, along with Sōkaku's willingness to spread this previously-guarded art form to the general public, the revised art of Daitō Ryū became very popular, and Sōkaku was crowned with the success of his idea as the chūkō no so (中興の祖; reviver or restorer) of the art.

According to Takeda Sōkaku, “the purpose of [Daitō ryū] is not to be killed, not to be struck, not to be kicked, and we will not strike, will not kick, and will not kill. It is completelyfor self-defense. We can handle opponents expediently, utilizing their own power, through their own aggression. So even women and children can use it. However, it istaught only to respectable people. Its misuse would be frightening…”

According to Takeda Sōkaku, “the purpose of [Daitō ryū] is not to be killed, not to be struck, not to be kicked, and we will not strike, will not kick, and will not kill. It is completelyfor self-defense. We can handle opponents expediently, utilizing their own power, through their own aggression. So even women and children can use it. However, it istaught only to respectable people. Its misuse would be frightening…”

Takeda Sōkaku produced several outstanding martial artists during his lifetime, among the best being Ueshiba Morihei-sensei, founder of modern-day aikidō. Morihei trained and taught Daitō-ryū Aikijūjutsu diligently during the years prior to WWII, while at the same time beginning development of his seminal aikidō style. After the post-war martial arts ban was lifted, Ueshiba-sensei resumed teaching aikidō, which he then continuously modified and refined until the time of his death in 1969. Shioda Gōzō-kanchō, one of Morihei's most revered students, studied seriously for eight years during Ueshiba's physical prime in the pre-war period.

*Daitō Ryū was known by the name Daitō-ryū jūjutsu until about 1922. Research indicates that the term aiki was added later to jūjutsu at the suggestion of Ōmoto-kyō leader Deguchi Onisaburō.

- Extensive conversations and notes from Obata Toshishiro-sōshihan

- Obata, Toshishiro. Samurai Aikijutsu. Los Angeles: Dragon Books, 1988.

- Pranin, Stanley A. "Encylopedia of Aikidō" by Stanley A. Pranin; Aikinews (1991).

- Pranin, Stanley A. "Aikidō Masters" by Stanley A. Pranin; Aikinews (1993).

- Pranin, Stanley A. "Daitō-ryū Aikijūjutsu." Aikinews (1996).

- Ueshiba, Morihei. Budō Training in Aikidō. Sugawara Martial Arts Institute, Inc., 1997

- "Aiki News: Daitō Ryū special issue." Aikinews Issue #79 (1988).