.jpg)

The Curriculum of Aikidō & Aikibujutsu

The Aikibujutsu Tanren Kenkyukai is an organization dedicated to studying the theory and applied principles of aikidō, aikibujutsu, and Edo torimonojutsu. These three main categories of study are applied in the areas of goshinjutsu (護身術; self-defense techniques) and taihojutsu (逮捕術; arresting techniques).

The Aikibujutsu section is subdivided into taijutsu (体術; empty-handed techniques) and bukiwaza (武器技; weapon techniques). Aikibujutsu taijutsu does not entail a competition of power against power, but instead involves taking advantage of an opponent's flow of strength to break his balance and apply a given technique. The objective is to control the opponent without injuring him; therefore, atemi (当て身; strikes) such as kicks and punches are used only sparingly. Aikibujutsu bukiwaza includes tantōjutsu, bokutōwaza (木刀技; wooden sword technique), jōjutsu (杖術; short staff technique), bōjutsu, and keibōjutsu (警棒術; techniques of the short stick or baton). The rokushakubō (六尺棒; long staff) technique is based on classical samurai methods as well as those of Ryūkyū Kobudō (classical Okinawan martial arts), and shares similarities with the handling basics of the yari (spear) and naginata (glaive). Keibōjutsu is a system of short stick techniques, which can be used in controlled hitting and thrusting, or to augment joint-lockingand pressure-point techniques. Bōjutsu and keibōjutsu are technical inclusions that are unique to our organization.

Training Philosophy & Practice Methodology

Out of concern for the issues of preserving traditional ways and offering adaptations and variations suitable to modern times, the attacking and defending methods have been modified when deemed appropriate. One example of this pertains to the practice of suwari-waza (座り技; kneeling techniques). There have been many cases wherein people have developed knee injuries while practicing suwari-waza; with this consideration in mind, more than 90% of the techniques in our curriculum are practiced from a standing position instead.

Techniques should be strong and effective, but students should keep in mind that the intention of aikibujutsu is not that of kakutōgi (格闘技), which refers to fighting for the sake ofbesting others in tournaments or showing one's strength or dominance. To train kakutōgi is to narrowly develop physical strength, and to establish a basis of winning or losing simply through the application of punching, kicking, or otherwise inflicting injury upon another.

Techniques should be strong and effective, but students should keep in mind that the intention of aikibujutsu is not that of kakutōgi (格闘技), which refers to fighting for the sake ofbesting others in tournaments or showing one's strength or dominance. To train kakutōgi is to narrowly develop physical strength, and to establish a basis of winning or losing simply through the application of punching, kicking, or otherwise inflicting injury upon another.

To study the self-defense aspect of martial arts toward the end of using it aggressively against others is the same as pursuing kakutōgi. If any learn budō merely as a tool for street fighting or testing themselvesagainst others, then they are not qualified to be learning budō in the first place. Budō must not be studied with the intention of injuring others or, worst of all, committing crimes or violent acts. Budō requires not only the study of technique, but that of a moral mind as well. Therefore, the heart and essence of a martial artist must needs be true and righteous.

Practice first starts with jūhō (柔法; flexible methods) and ryūhō (流法; flowing methods), comprising the softer aspects of aikidō, in order to develop a sense of harmony between partners and to drill basic ukemi (受け身; rolls and breakfalls). After learning to perform safe ukemi, one moves on to studying aikibujutsu and Edo torimonojutsu, which comprise the gōhō (剛法; harder methods). When training torite-waza (arresting techniques), the opponent will not cooperate; therefore, the techniques and movements are made more realistic and include advanced atemi and footwork. Using techniques that involve strength and applying one's full power against the opponent's joints in controlling and locking techniques can be very dangerous. One can easily injure another's joints, so it is important for partners to practice carefully with each other.

Practice first starts with jūhō (柔法; flexible methods) and ryūhō (流法; flowing methods), comprising the softer aspects of aikidō, in order to develop a sense of harmony between partners and to drill basic ukemi (受け身; rolls and breakfalls). After learning to perform safe ukemi, one moves on to studying aikibujutsu and Edo torimonojutsu, which comprise the gōhō (剛法; harder methods). When training torite-waza (arresting techniques), the opponent will not cooperate; therefore, the techniques and movements are made more realistic and include advanced atemi and footwork. Using techniques that involve strength and applying one's full power against the opponent's joints in controlling and locking techniques can be very dangerous. One can easily injure another's joints, so it is important for partners to practice carefully with each other.

In the dōjō, basics are practiced repeatedly, and partners will accommodate each other; outside the dōjō, however, opponents will not cooperate with one's movements. Techniques practiced in the dōjō and techniques that work in real situations outside the dōjō are different, so it is important to learn basic technique thoroughly in the dōjō to understand this completely. Advanced students should research techniques and learn technique variations. One can adapt these techniques by using these variations to address each unique situation, which then produces realistic and effective techniques for self-defense.

|  |

|  |  |

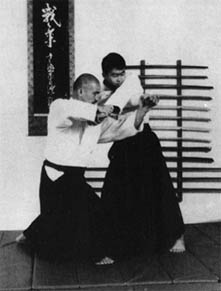

| A ryōtedori (double hand-grab) technique of taihojutsu (arresting methods) | ||

Buji Kore Meiba

When horses went to war with their masters on their backs, one might have assumed that lining up bravely on the front line would have been considered the main asset of a good horse. However, the sayingbuji kore meiba (無事これ名馬) means that a horse ought to bring home its owner safely from the battlefield. Even if the horse were brave, if it were injured by an arrow or bullet, or fell and broke its leg, then the rider of the horse could not fight, and was therefore in more danger. As a result, it was important that both rider and horse were not injured.

The same can be said for martial artists. In modern times, martial arts are generally not studied for use in life-or-death encounters as they once were in years past. Therefore, if a practitioner becomes injured during practice or a competition and is not able to continue practicing in the future, or develops some type of limitation that affects his daily life, he will likely come to regret having ever studied martial arts. It is important to practice martial arts without getting injured. By practicing for a long period of time — not rushing, but at one's own pace — one can expect to gain strength and stamina, maintain one's health, and develop techniques suitable for self-defense.

Seishin Shugyō

In budō, one must not only train physical techniques. Seishin shugyō (精神修行), or spiritual and mental training, is also very important. In our arts of Aikidō and Aikibujutsu, Shinkendo, and Toyama Ryū, one studies the philosophical doctrines of Kuyō Junikun (九曜十二訓; the Nine Planets & Twelve Precepts) and Hachidō (八道; the Eightfold Path) for spiritual and mental training, along with various other moral and spiritual teachings. Kuyō Junikun contains twelve precepts of martial arts study that are also are applied in daily life, and can be used toward improving oneself both as a martial artist and individual. Hachidō is the study of the self and world around us, and how to understand and live well among others. Along with these doctrines, bushidō (the way of the samurai), reihō (etiquette), and other disciplines are taught.By studying and applying these philosophies, one comes to better understand our role in the world and how the study of budō improves one's spirit and character, and becomes a source of benevolenceto others and society.

|  |  |

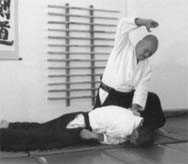

| Several different nagewaza (投げ技), or throwing techniques | ||

Waza no Bu

Aikibujutsu Taijutsu Waza

Aikibujutsu taijutsu techniques are divided as follows:

- Aikidō Waza

The basic techniques comprising modern aikidō. - Te-hodoki Waza

Te-hodoki waza (unbinding methods) consist of techniques used to reverse situations in which one's wrist or hand is grasped. Basic te-hodoki consists of six kagami (鏡; mirror), te-kagami (手鏡; hand-mirror), ten (天; heaven), chi (地; earth), jun (順; obverse), and gyaku (逆; reverse) methods. From te-hodoki, one moves into osaewaza (controls), nagewaza (throwing), and katamewaza (固め技; locking or grappling). - Torite Waza

Torite waza consists of arresting techniques that are employed before being attacked, or for arresting those who appear suspicious or are believed to be carrying weapons. These are effective arresting techniques used by law enforcement and security personnel. Despite the severity of a given situation, one may risk being charged with use of excessive force if one assaults a suspect's face with kicks or punches, causing “violent” injuries. It is therefore important not to rely on excessive kicking and punching methods that can cause injury (broken teeth, broken nose, etc.); instead, one should use controls or locking techniques to limit an opponent's movement and then subdue them for the arrest. The goal of torite waza is to facilitate quick, safe arrests (for both officer and suspect) without causing injuries to the aggressor. Advanced atemi and footwork are employed as hojo waza (補助技; supporting techniques) in order to strengthen the torite waza. - Renzoku Nagewaza

Renzoku nagewaza (連続投げ技) are combined throwing techniques that are categorized into yukiai (行合; in passing), kaiten (回転; turning), and te-awase (手合わせ; blending with the hands) methods. By learning to combine nagewaza, one will be able to control one's breathing, learn natural footwork and body movement, and move naturally into freestyle techniques. - Kaeshi Waza

Kaeshi waza (返し技) are reversal techniques. When an opponent moves in to apply a technique, one performs a reversal movement and applies a counter-technique.

Aikibujutsu Bukiwaza

Aikibujutsu bukiwaza techniques are divided as follows:

- Bōjutsu

Bōjutsu involves the use of a six-foot staff that combines Obata-sōshihan's original techniques with traditional Japanese techniques and Ryūkyū Kobudō methods. Bōjutsu requires extensive twisting of the body, so one develops softer and more flexible shoulder and hip movements that are useful for aikidō, shinkendo, and other budō. The suburi (swinging) techniques are split into shōkyū, chūkyū, and jōkyū (basic, intermediate, and advanced) levels. By practicing at each level, one can analyze and understand the complicated movements comprehensively. Bōjutsu also involves kamae, attacks, blocks, solo kata, and paired kumite, and serves as an important basic foundation for other weaponry styles, such as the naginata and yari, which are longer polearm weapons historically. - Jōjutsu

Jōjutsu are short staff methods, which include paired kumite, striking and blocking methods, and arresting methods. - Tantōjutsu

In tantōjutsu, one learns knife techniques that based on traditional Japanese tantō methods, including paired methods and classical defenses against knife attacks. - Bokutō Waza

The bokutō waza are not a system of sword technique in itself, but are wooden sword methods that include paired body movement exercises. - Keibōjutsu

Short stick techniques, or keibōjutsu, include strikes, blocks, joint locks and arresting methods. The keibō is a small, verstaile weapon that could easily be hidden in one's kimono sleeves.

|  |  |

Mutōdori & Shinken Shirahadori

Mutōdori (無刀捕; unarmed techniques against a swordsman; literally, "swordless capture") that involves bare-handed controls or throws to take away the sword from an attacker is not only practiced in aikidō but in other martial arts as well. When the attacker or uke (受け; person who receives the technique) swings a sword or a bokuto with a straight cut, the defender or shite (仕手; person who performs the technique) moves his or her body in such a way as to control or throw the uke. When the uke makes a big swing back into the jōdan position (sword above or behind the head), the shite grabs the uke's wrists or arm in order to apply a technique. These techniques can only be done if there is perfect harmony and a cooperative relationship between shite and uke. In other words, the uke makes it easy for the shite to apply a technique. Mutōdori cannot be successfully applied to people who have learned swordsmanship or to people who lack formal swordsmanship experience and swing the sword at the shite in a random fashion. Mutōdori is said to have originated from Yagyū Ryū, but it would be wiser to catagorize these almost impossible techniques as entertainment appropriate to movies or for provoking the imagination.

The main reason it is too dangerous for a bare-handed person disarm a swordsman is because the distance and speed are vastly different between an unarmed person and a person with a sword. A sword need not only swing straight down — swordsmanship involves diagonal cuts, horizontal cuts, reverse cuts, thrusts, etc. that target various parts of the body. A swing line can change to an entirely different swing line in an instant. The dubious techniques found in mutōdori suggest that it is conceived upon an unrealistically limited or naïve view of swordsmanship.

The main reason it is too dangerous for a bare-handed person disarm a swordsman is because the distance and speed are vastly different between an unarmed person and a person with a sword. A sword need not only swing straight down — swordsmanship involves diagonal cuts, horizontal cuts, reverse cuts, thrusts, etc. that target various parts of the body. A swing line can change to an entirely different swing line in an instant. The dubious techniques found in mutōdori suggest that it is conceived upon an unrealistically limited or naïve view of swordsmanship.

Shinken shirahadori (真剣白刃取り; techniques for seizing a live-blade; literally, "white-edge capture") are techniques in which the shite grabs the attacker's sword blade as the attacker swings straight down. Even though teachers and students have established and practiced the required timing, stopping position of the sword, etc., there have been many incidents in which the person performing shinken shirahadori has cut his or her palms.

To teach that mutōdori and shinken shirahadori are viable or real techniques if practiced long enough is the same as teaching one's students techniques for suicide.

Aikidō movements are commonly believed to have originated from Japanese swordsmanship. Therefore, the Aikibujutsu Tanren Kenkyukai recommends that higher-ranked aikidō practitioners learn the comprehensive, practical sword art of Shinkendo, as it will complement one's study of aikidō. Among other things, practitioners who study Shinkendo will understand that bare-handed sword take-away methods are simply misleading, unlikely, and reckless techniques.